The Trilogy

By Daniel Mufson

Abdoh regarded The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice (1990), Bogeyman (1991), and The Law of Remains (1992) as a trilogy. Why these three could be considered to be more closely related than the other plays is not immediately clear—when asked why she thought of them as a trilogy, producer Diane White would only say “They’re a trilogy because Reza thinks of them as a trilogy.” On tour in Paris, the first and third of the series were actually presented with Tight Right White, as Bogeyman was too expensive and complicated to re-mount. The new mix struck at least one critic, Philippa Wehle, as not at all unsatisfactory. “All three plays,” she said of Hip-Hop, The Law of Remains, and Tight Right White, “question the precarious nature of identity—racial, gender, class and otherwise.” Bogeyman, considered by both White and Abdoh as the playwright/director’s most personal and spectacular work, has faded into the background as the one-shot production that closed the LATC, a production that never toured with its siblings and was never seen anywhere but in L.A.

In spite of the unobviousness and economic infeasibility of their presentation as a trio, it might be worthwhile to discuss the plays in their originally intended relationship. If nothing else, they fall in tight chronological order and offer a testimony to the quick versatility of Abdoh’s imagination. Although Abdoh never articulated his own reasons for calling the three plays a trilogy, there should be no doubt that the classification was certainly not a post hoc label arbitrarily applied. In his program notes for the Bogeyman, Doug Sadownick indicated that, at least as early as that show, Abdoh considered himself at work on a trilogy.

What would seem to bind the three is a more extended and focused attempt at exorcising sexual demons. In addition, when political issues are dealt with, there is more of a tendency to make explicit references to contemporaneous figures and events. It is in the trilogy that there are the most explicit references to American political figures and currents: Ronald Reagan and George Bush appear or are referred to in Hip-Hop and The Law of Remains, and the governor of California, Pete Wilson, is referred to at the end of Bogeyman, along with an allusion to HB101, the antidiscrimination bill for gays and lesbians that was being considered at the time. But the main thing that binds the three more than the other shows is the primary concern with sexual repression and the categories of sexual normalcy and aberration. A sexually repressed state is the setting for Hip-Hop; homophobia and the trials of an outcast gay son fuel the narrative of Bogeyman; and the focus of The Law of Remains is Jeffrey Dahmer, whose murders were noted for their involvement of sexual, and, moreover, homosexual abuse. Abdoh says that his experiences and the performances he saw at a now closed S&M club, called FUCK!, influenced some of the scenes in Bogeyman and The Law of Remains. Some of the actors in Bogeyman did performance work at FUCK!, including Cliff Diller, who was actually one of the club’s co-founders and has also since died of AIDS. The influence of Club FUCK! and sadomasochism’s leather, latex, and rubber fashions are markedly less prominent in, if not altogether absent from, all the productions before and after the trilogy.

Sex and death are involved in the other works, too, but Tight Right White focuses more on ethnic than sexual identity and is slightly more oblique in its political references to contemporaneous figures or events. Quotations, too, certainly deals with sexual issues in the scenes that follow a gay couple, but the performance is a broader look at history and the placement of individuals within a society’s history. Quotations deals far more with the institutionalization of violence in war and capitalism.

The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice

The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice begins in silence. Two characters, Orpheus and Eurydice, separately go about their own activities in a huge, white room, a space that is antiseptic in spite of the water-stained floor. A kitchen area—really just a sink with an assortment of pots and pans—sits upstage right, and a large bed lies center stage in front of a video screen that, to begin with, is designed to look like a window. Not a word is spoken for the first 10 minutes of the show. Aside from a bell’s intermittent chiming, we hear only the sounds associated with the characters’ actions and surroundings—of Orpheus working at his typewriter, of a dripping sink, and, at one point, of Eurydice urinating into a bucket.

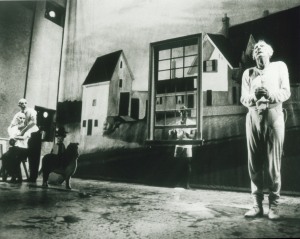

“The Interrogation Scene” from Hip-Hop. Photo: R. Kaufman.

Eurydice and Orpheus are played by Tom Fitzpatrick and Juliana Francis, respectively—they’re in drag. Fitzpatrick is walking around in black negligée, while Francis, wearing a white tee shirt and slacks, types on a typewriter, listens briefly to indecipherable sounds on an old-fashioned radio, or gets shaved by Eurydice. Both characters are pale, bald—heads cleanly shaved, and not wearing bald caps. They look gaunt and possessed. They each wear their portable mikes fastened on their neck with what looks like thick layers of white tape—as a result, both of them resemble automatons whose heads would pop off if you unscrewed them.

Various images appear in Hip-Hop that recur in later shows or The Blind Owl. Intermittently throughout the play, a character will say: “We’re making a movie, and you’re the star!”, an idea that will be echoed by Moishe Pipik’s refrain in Tight Right White, “We’re searching for that gem of a tale to tell on TV.” Each phrase lends a feeling of self-consciousness to the depicted struggle; each reflects an impulse to locate hardship and suffering in order to exploit them for their value as narrative—an interesting presence in a show created by a man with AIDS. In both productions, the person who most often says the line is a demon character, an obese fat man, a selfish and imperious hedonist. The father in Bogeyman is also of this ilk.

Other images from Hip-Hop that recur elsewhere are simpler: For instance, Eurydice burns her hand on a pot, opening a moment for Orpheus to perform a moment of tenderness, crossing the stage in silence to kiss her hand and rest her cheek on it. A variant of this image and moment happens in The Blind Owl.

In Hip-Hop, this moment of tenderness almost leads to a kiss between Orpheus and Eurydice, but the impulse is interrupted by the sounds coming from the couple next door. A woman is asking for sex; the man is reluctant—“What do you want to do, get me in trouble?” The man submits, and the subsequent groans of ecstasy are interrupted by the loud sound of a car screeching; suddenly we hear an unseen man interrupting the couple next door, his voice heard against an incongruously slick jazz saxophone: “Tame Eros. We will cure you of your perversions. You return to your dung as a dog to its vomit. C’mon, boys, throw her out the window. Lights out!” And the stage goes dark. A similar fate will come, in more horrific detail, for the two protagonists.

But first, the scenes that follow afterwards create a bickering chemistry between Orpheus and Eurydice by transposing the style of situation comedy cum vaudeville routine onto the mythic status associated with the two figures—a variation on Cocteau’s decision to put the two in the domestic, humdrum setting of his Orphée. Fitzpatrick and Francis perform the scenes presentationally and against the occasional entrance of two black men, Brazilian singers and capoeira dancers who run in and, in these early scenes, stand stationary with dog collars on their necks, leashes leading to their offstage origins, as they sing a Brazilian tune. On two occasions Eurydice responds to the singing by exclaiming, “Oh, I just love that Xavier Cougat!” At the climax of the bickering, after Orpheus tells Eurydice it would serve a burglar right if he broke into the house and found her alone, the Brazilian singers break into their loudest and fastest-paced song as a special shines on Orpheus, who performs a remarkable dance that consists of smacking himself rhythmically on the shoulders, chest, and head.

The scene again falls dark and quiet. In the darkness we hear a slow whistling, as two specials dimly light the husband and wife. Eurydice, stimulated by the whistling, lies on the floor and asks Orpheus to have sex with her. It looks likely that the two of them are about to embark on the same unfateful course taken by their neighbors. “Fuck me now,” Eurydice says, as wolves howl in the background. “You know I can’t do that! Do you want to get me in trouble? Shut up, shut up now!” Then, Orpheus sings: “I do not know with whom hated will sleep, but I do know the hated will not sleep alone.” And there is a moment of near-silence before the scene erupts into a storm of sound and movement that has, for many, become Abdoh’s trademark.

A character alternately known as “Boss-man” or “Captain,” enters. He’s utterly grotesque, obese, with lesions and sores on his face, a lurid smile, wearing a white suit. Played by an LATC actor, Alan Mandell, rather than one of Abdoh’s Dar A Luz company members, the Captain enters and begins a racing, brilliantly repulsive performance that forms the heart of the show. Hip-hop dance music thunders as the Captain’s assistants, wearing welding masks, somersault into the playing area to grab Eurydice and Orpheus. The Captain follows them, yelling orders.

An arresting statue of a woman appears on stage. Eurydice is carried off, and the Captain and Orpheus have an incongruous exchange, where the two adopt the dialogue of a sexual harasser and his victim—over the course of which, the Captain ties a huge dildo onto Orpheus (this exchange is mirrored in a later exchange between the Captain and Eurydice, where Eurydice is given a pair of fake breasts to wear). When Orpheus tries to run, the Captain lassoes him, throws him on the bed, and, in the most nightmarish delivery possible, growls, “We’re gonna bore desire right out of you.” Sudden darkness, followed by whistling: Eurydice’s face, far upstage, appears dimly lighted, until a flying object rips off the head of the statue—and we slip further and further down a frenetic descent into hell. Yet the descent is not direct and clear cut; bizarre, occasionally comic but always disturbing exchanges are laced through the interactions that are more recognizable as occurring between Orpheus, Eurydice and the Captain.

The exchanges that do not clearly relate to Orpheus and Eurydice are not, however, desultory. The way in which different threads are introduced, submerging and resurfacing in some mystical, unknowable pattern, is one of the remarkable aspects of The Hip-Hop Waltz of Eurydice. Fragments of sexual harassment scenarios, of TV sit-coms and vaudeville, of discussions about plastic surgery and violent torture, zip around the central narrative like electrons around a nucleus, occasionally penetrating each other’s orbits while maintaining an air of autonomy. On a small scale, Abdoh’s manipulation of disparate threads into a fabric that somehow makes sense is exemplified in the following magnificent monologue, superbly delivered by Alan Mandell. He delivers it to the audience soon after he allows Orpheus to take Eurydice back to the realm of the living, on condition that “you can’t desire to fuck her.” Mandell delivers the monologue against the intermittent sound of an adagio piano sonata, a constant stream of images on the large video screen on the back wall, and occasional, sporadic movement from a naked Eurydice and the Brazilian dancers. It’s a long monologue, but it deserves to be read in full because it has a remarkable hold on the interest for such a lengthy speech, both in spite of and because of its disconnected-but-connected organization, and because it will facilitate an understanding of the literary style of Hip-Hop and the rest of the trilogy.

THE CAPTAIN : Anyone want a shave and a haircut? A close shave? Anyone want a haircut? You—do you believe God will touch you? I want to avoid a face lift. Does it make sense for me to do facial exercises, like, um, clenching my teeth, and so on? One of the things about male Oriental boys: when you buy them, their body is yours, to do with whatever you want. Roger, Roger, she died three months ago, you showed me a copy of the death certificate, don’t you remember? This one, I know, was old enough to know the score [laughs.] and had been to the bar before, so, so, we go in. We go in and have another beer. “Where’s my blue lady? Where’s my blue lady? Where’s my—” My blue lady has vanished, she’s gone. Well! love’s going to get her. And love’s going to get you. And love is going to get you! Always be as well dressed as your circumstances will permit. These are the answers—remember these answers: #1, Masda; #2, Citizen Kane; #3, Quantum mechanics; #4, forty-eight pounds. Remember! So…I slipped this guy another five, and he’s all smiles. Well, I wasn’t going to stand around looking like a freak, so I started undressing. And I ordered the kid—his name was, mmmmm, uh, Safi, to do the same. [To unseen person upstage, when the piano music stops:] Why are you stopping, why are you stopping, don’t stop, don’t stop, go, Go, GO! [Pointing to different members of the audience:] Tonight: you will be robbed of your Rolex, you will crash the car, your house will burn down, your baby suffocates in its crib, the babysitter gets stoned, there will be an earthquake, Iraq has the atom bomb, the ceiling above you will collapse, the man next to you is going crazy, your wife wishes to murder you—

Alan Mandell as the Captain. Photo: R. Kaufman.

ORPHEUS: [unseen, these words overlapping the Captain’s:] Liar, liar, liar, liar, liar!

THE CAPTAIN: [Still to the audience:] You will lose your dog. #5, Islam! Remember! #6, the fatal flaw, #7, wise man. #8, après moi le deluge, REMEMBER! [sudden stop, and silence] I have a card, a card here in my pocket with something printed on it, and I would like someone to read it in a loud clear voice. Would you like to read it, for all of us to hear? You can read it right into my chest, here. AUDIENCE MEMBER: I am a self-starter. I enjoy and am excited by producing. THE CAPTAIN: WE’RE MAKING A MOVIE, AND YOU’RE THE STAR!! You believe that? [Laughs.] Busy young creatures, you don’t stand a chance! So we all get up. And I order beers for me and my whore. Well I got my drink, and I took Safi over to a small table by the wall and had him start sucking. JUDAS IS POSING WITH THE BEE-GEES IN A WHITE LEISURE SUIT. NO-ONE, no one, could replace Andy Gibb. Ashes, whiskey, and tears.

EURYDICE: Do you know “Mrs. Miller’s Greatest Hits”? I miss you. Come and get me.

THE CAPTAIN: I don’t want him to go. My memory is failing, my bladder is weak, my arches are falling, my tonsils and adenoids are gone, my jawbone is rotting, and now my little boy wants to leave me and cast me away. I’ll end up in a geriatric ward, I’ll have to take enemas, I WILL BE INCONTINENT. There’s a heart miracle taking place! You! Stand up, put your hand over your heart, and call that a miracle. You lift up your head and call that a miracle. Tonight’s my night for a miracle. Tonight’s my night for a miracle. Tonight’s my night for a miracle. Tonight’s my night for a—

EURYDICE: Do your flower beds have barren or weed-choked areas? Do they lack color?

THE CAPTAIN: Oh, shut up. Chico, you’re sooo groovy. Well, about the same time this marine started busting his nuts in this guy’s ass. And one of the sailors got up on a table and told the kid to suck. his. cock. You with glasses: Am I neurotic for wanting a face lift? #9, the Tower of London, #10, you could have had a V8—REMEMBER! #11, Dietrich Bonhoeffer. [Sudden quiet.] What…if Noah had failed? [A wolf howls. Then, quietly:] A lady may remove her gloves or not when partaking of supper. Guests do not bid their hostess goodbye. They quietly, very quietly, withdraw.

EURYDICE: As you examine your personal landscape do you see anything else you don’t like or would like improved?

THE CAPTAIN: Oh, shut up. Boy, I couldn’t take it anymore. I started busting my nuts, and Safi started sucking cum from my cock—till I was weak! [Sings:] Oh, love, your magic spell is everywhere, love, I saw you and I knew you cared. [Suddenly, breathlessly, returns to speaking:] They had this bottle of rice wine, I started drinking it, I got drunker than a coot. We are as driven to kill as we are to live and let live, isn’t that so? I heard that. I picked up this bottle and smashed it in his face. He dropped to the ground. Everyone turned; no one said a word. Round and firm and fully packed, I crowned the Shenandoah Apple Queen! Listen, men don’t get smarter as they grow old. They just lose their hair, isn’t that so? I know that. [He adjusts his wig. The piano playing halts.] Why are you stopping? Why are you stopping? Don’t stop, don’t stop, go, Go, GO! You see, healing is like ringing the dinner bell to lure sinners to salvation. Isn’t that so? I heard that. Before you kill somebody, make sure he’s well connected. “Here lies old Fred; it’s a pity he’s dead.” I am obsessed with the little toe on my left foot. It’s turning into a claw. A SPECIES THAT IS GOING NOWHERE! And I’m having to do this alone! Not like Cousteau, with his assiduous team aboard the sun-flooded schooner, but here, alone. Alone. Alone. These are the questions, let’s hear the answers: #1, what name is shared by the Zoroastrian god of light and a popular car? #2, what film was consistently booed at the 1941 Academy Awards? #3, What does the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle apply to? #4, What did Oprah Winfrey lose? #5, What is Arabic for “submission to God’s will?” #6, What did Louis XV never really say? #7, where were the little princes kept? #8, Who said that religion should take place in the market place of life? #9, What is the phrase which illustrates the economic principle of opportunity cost? [Pause.] You could’ve had a V8! YOU FUCKED UP! [We hear Orpheus’ scream, artificially sustained into a note that plays along with a ballroom dance.] I should like to cut off a dead man’s member, and have it sewn on to me. I should like to be a man. I should like to rob a dead man’s soul before it went to heaven, and turn myself into a man. I would then seduce all women. I want to taste everyone and every word. I believe I am too good for this calling. I should like to wallow in something, just to say that I wallowed in it. I know it. I should like to wallow in corpses. I want to be stronger and stronger. I’ve never had a facial injury; I should think I’d go mad if I did. Is my body now obsolete is my body now obsolete is my body now obsolete [a deep voice echoes over: “obsolete, obsolete, obsolete” then stops] my body’s now obsolete my body’s now—[He stops suddenly as he opens a child-size coffin. The music drops out and all we hear is Orpheus’ scream/note. Lights dim, and we see only a video image of the coffin being thrown out a window. Segue into the next scene.]

Many threads run within the above monologue, some of them surfacing only as refrains or reminders of something said or alluded to elsewhere in the show. The “shave and a haircut” questions, for example, come up elsewhere in Hip-Hop, and don’t overtly connect to anything; they do, however, have a comic absurdity in a world where physical appearance is topsy-turvy to begin with and the trivial level of questions suddenly begins to intrude upon a larger-than-life struggle. The references to plastic surgery hook up to other references, usually comic, elsewhere in the play; the “We’re making a movie” line has already been mentioned, as well.

Several motifs establish their own rhythm within the speech alone. The anecdote about the Asian catamite runs intermittently throughout, as do the mostly satirical “Trivial Pursuit” types of questions and answers. Images of physical deterioration and deformity are rife, starting with the “my memory is failing” section, and coming again in the lines about men losing their hair, the claw that’s growing on the Captain’s left foot, and the section on cutting off another man’s penis that climaxes, as it were, in the repeated remarks about his body’s being “obsolete.” There is an alternately self-pitying and bitter subnarrative that hints at encroaching isolation and personal loss—the loss of memory and a [presumably] woman loved by someone named Roger, and the “I’m having to do this alone” moments.

The wolves howl and the Captain shivers as the lights slowly fade. Photo: R. Kaufman.

All of these intersect with each other in an indirect way: the sense of loneliness and alienation that is both prerequisite to and part of patronizing prostitution; the experience of the narcissistic vision of love that creates a compulsion for plastic surgery; friction between the Captain’s insatiable hedonism and society’s capitalism, the latter of which is mocked in the card read by the audience member and in the simultaneously satiric jabs at opportunity cost and the marketing of V8 juice. Most interesting, though, is the way the speech incorporates an anger and disgust at a sexually repressive figure at the same time that it portrays that figure’s hypocritical indulgences as something repugnant. The paradox is not confined to the speech. Much energy is spent, in Hip-Hop and other shows, violating societal and stage taboos on the depiction of human bodies, sexual activity, and gender preference. And yet at the same time Abdoh lashes out at the violence inherent in declaring these things forbidden, the forbidden things themselves are often portrayed in a dark, unattractive light. One would be hard-pressed to argue that Abdoh’s shows are “sex-positive”; they’re critical of both sex and sexual repression, and sometimes it’s difficult to differentiate between the two. But this is part of what makes the shows so disturbing—they don’t resolve this paradox, and even when there is a gesture at redemption, which so many critics try desperately to latch onto, the gesture is devastatingly compromised by the horrors that have preceded it.

Bogeyman

2 Corinthians 4:8-10 speaks of humans “troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; cast down, but not destroyed; Always bearing about in the body the dying of the Lord Jesus, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our body.” St. Augustine, using the Old Latin version of the Bible, cites this passage in the opening of his Confessions when speaking of humanity “bearing his mortality with him.” While this passage doesn’t directly bear on Abdoh, who was not Christian, it expresses eloquently a struggle that can exist for anyone who suffers, for anyone aware of his or her own mortality—a struggle highlighted in thinking about artists with AIDS: Does one feed off the part of the soul that is distressed, or that which refuses to despair? Artists with AIDS bear a mortality within themselves, and this has had consequences, frequently discussed, for the creation of art at the end of the twentieth century.

Most often, the result has been a choice, by those bearing their mortality with them, to refuse distress, to refuse despair, to forsake feelings of forsakenness. In her book of interviews with HIV+ artists, Muses of Chaos and Ash, Andréa Vaucher asked Reza Abdoh to comment on the following remark by the HIV+ painter, David Wojnarowicz: “I think anybody who is impoverished in any way, either physically or psychically, wants to build rather than to destroy.” Reza responded,

In a time of chaos, and in a time when one’s body is subject to deterioration, I think it’s a natural impulse to want to create and build rather than to continue to destroy. Of course, though, for that to happen, you also have to destroy. I believe that. I don’t believe you can put shit on top of shit.

That willingness to explore feeling perplexed, distressed, forsaken, and, ultimately, incredibly angry, is half of what differentiates Abdoh from so many of the more insistently affirmative HIV+ artists. The other half is his determination that “it has been very important for me not to permit [the impulse to redefine yourself because of AIDS] as a tool for self-pity.”

As a consequence, what Charles Marowitz criticizes in Bogeyman is also part of what makes the show so remarkable—and Marowitz, to some degree, concedes this. “What is fascinating about this piece,” he writes, “is the unmitigated quality of Abdoh’s inferno…This is also its greatest weakness for it occasionally has the quality of a child’s tantrum…too engrossed in condemning evil to work out a strategy to combat it.”

Bogeyman tells the story of Billy, played by Peter Jacobs and not overly dissimilar to the character in The Blind Owl named Ricky, played the same actor. The narrative follows Billy as his family reacts to the revelation of, first, his homosexuality, and second (and more ambiguously), his stay in a hospital as a result, presumably, of AIDS. The story is an outline to be departed from, a vessel into which Abdoh tosses anything that will fit. The true focus is not a narrative; the narrative is a pretext for exploring modes of human cruelty—those that are identified as taboo, and those that pass unquestioned as part of the “normal” conduct of everyday life.

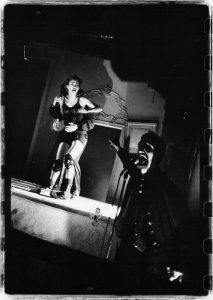

Bogeyman. Photo: Jan Deen

Bogeyman is an extreme example of split focus, where multiple scenes of sadism and masochism are explored simultaneously. The set is dominated by a three stories high apartment building shown in cross-section, divided into at least nine rooms, and there is also an open playing area in front of the façade. At any given moment, scenes may be playing in three or more areas. One room looks like an average household; others show a Midwestern plain and a scarecrow, an S&M club, a dilapidated apartment, an upside-down hospital room, a hunting ground in a forest. The simultaneously played scenes are not performed in silence or anything approaching it. Monologues and dialogues overlap, although usually one scene is somehow given prominence, either through brighter lighting, higher volume, or both. The attention is further split by a profusion of video screens—three of them the size of TV’s, one of them the size of a small movie screen.

The effectiveness of the split focus is difficult to judge by the video I have of Bogeyman. More than was the case with any of the other shows, whoever took the video was forced either to make choices in terms of what to focus on or to pull back for as broad—and literally unfocused—a picture as possible. The sense of disparity between the video and what must have been happening in the theater is heightened by audience reactions that imply unseen action.

Dulle Griet

In his essay, “Blocking Brecht,” Maarten van Dijk discusses Brecht’s conception of blocking as montage; whether or not he took it from Brecht, Abdoh has fully assimilated this idea in all of his work, for theater and in The Blind Owl. He is not only expert in the sequential juxtaposition of jarring images, which Franco Ruffini called horizontal montage, but in montage within a scene—the Brueghel Effect, or what Ruffini called vertical montage. Abdoh used both in all of his productions, but the frequency of the latter reaches its apex in Bogeyman. The inspiration for Abdoh’s use of montage could have been Brueghel, or Brecht (inspired by Brueghel), or the tradition of Persian miniatures. Referring to paintings such as The Fall of Icarus and Dulle Griet, Brecht wrote,

Such pictures don’t just give off an atmosphere but a variety of atmospheres. Even though Brueghel manages to balance his contrasts he never merges them into one another, nor does he practice the separation of comic and tragic; his tragic contains a comic element and his comedy a tragic one.

From the Shahnameh epic

In the reproductions of Brueghel’s Dulle Griet and a Persian miniature from the sixteenth century illustration of the Shahnameh epic, and one can notice that, although the manner of figurative drawing is different, the element of split focus is common to both. Bogeyman actually maintains a more rigorous visual compartmentalization than either of these two paintings, but the principle is the same: to invite a wandering eye and a consequent consideration of how discrete events and entities bear a relation to one another.

Bogeyman is angrier than Hip-Hop. Where the latter more often played soft or quietly eerie music against a disturbing monologue, Bogeyman blasts distorted guitar riffs. Much more of Bogeyman is shrill—it seems like the actors spend a lot more time in this show just shouting to be heard. The only thing that seems beyond question is that the show is, technically speaking, miraculously complex, with hundreds and hundreds of sound and light cues that whiz by at incredible speed. Even when it’s impossible to really discern what’s happening in the cacophony, the cacophony is clearly orchestrated in such great detail that it is interesting to watch for that alone.

And yet one can discern moments of beauty: a male naked corpse lies with its face covered, downstage right; a kneeling person, barely visible in the shadow, caresses its leg; meanwhile, on a platform upstage left, a woman in black twirls around and around against the sound of an opera and a person saying: “I am Rachel of old, I am Rachel of old, I am Rachel of old…I am Rachel of old weeping for my children…” She presents an inverse image of the whirling dervish, customarily dressed in white, for purity, and yet the invocation of the dervishes, spinning in part to relinquish their ties the temporal world, seems somehow appropriate to the mentioning of inconsolable Rachel. The twirling woman collapses and the mourner leaves, removing the towel that covered the corpse’s face—and suddenly the corpse is no longer a corpse, but alive, naked, stunned, and shivering. The invocation of Rachel happens elsewhere, too, and she is an apt figure to be summoned in Bogeyman: the wife of Jacob, a figure of lament invoked in the books of Jeremiah and Matthew, the woman who wept and would not be comforted, for her children were not. She is an emblem of the selfless mother concerned only for her children—she died in childbirth. But in Jeremiah and Matthew, her obstinate concern for her children was invoked before presaging better times.

The idea of inconsolable but somehow finite sorrow enters later in Bogeyman, in a performance of “The Weeping Song” (originally by Nick Cave). Shortly after one of many scenes of domestic discord, in which, among other things, the mother figure shows her self-hatred by exposing her genitalia and telling everyone to “feast” their eyes on her “ugliness,” most of the male members of the cast gather and sing,

Now, son, go down to the water, and see the women weeping there.

Then go up into the mountains, the men—they are all weeping, too.

Father, why are all the women weeping?

They are all weeping for their men.

Then why are all the men there weeping?

They are weeping back at them.

This is a weeping song, a song in which to weep, while all the men and women sleep.

This is a weeping song, but I won’t be weeping long.

Father why are all the children weeping?

They are merely crying, son.

Oh, are they merely crying, Father?

Yes, true weeping is yet to come.

This is a weeping song, a song in which to weep, while all the little children sleep.

This is a weeping song, but I won’t be weeping long.

Oh Father, tell me are you weeping? Your face, it seems wet to touch.

Oh, I am so sorry father, I never thought I’d learn so much.

This is a weeping song, a song in which to weep, while we rock ourselves to sleep.

This is a weeping song, but I won’t be weeping long.

No I won’t be weeping long, no, I won’t be weeping long…

Bogeyman. Photo: Jan Deen

The song is ambiguous and chilling: “I won’t be weeping long,” is sung in a low, determined tone, and it sounds as though the singers are determined that things will get better. At the same time, the middle verse advises that “true weeping is yet to come.” The final verse also ends with the father figure, who had hitherto seemed a more sedate and detached authority on weeping, breaking down himself. If considered with an awareness of the playwright’s condition (shared by the foregrounded singer of the group, the late Cliff Diller), then the implication is that the weeping will indeed end—by death. As usual, Abdoh offers a promise of redemption, but surrounds it by hints—textual, performative, and in contexts beyond the theatrical experience—that the redemption will not be unadulterated.

Compromised miracles occasionally make themselves known comically in Bogeyman. Towards the end, a fairy godmother—played by the transsexual performer, Sandie Crisp, speaking in an incredibly gravelly and raspy voice—appears to the harrowed mother, played by Juliana Francis. The fairy godmother tells Francis to guess who she is. “Louis Armstrong?” Francis asks. Francis gets it right on her next guess, and, upon making a wish, the screen of the Midwestern plain, which Francis is standing in front of, falls to reveal another screen with a large, naked derrière painted on it. From out of the butt crack emerges a human-sized frog, wearing a crown. “Should I kiss him?” Francis asks. The audience shouts yes. The frog becomes a prince, ludicrously played by Tom Fitzpatrick (who has, until this point, played the sadistic, bigoted, and psychotic father figure). Francis asks him who he is, and he responds:

I’m your Prince Valiant. In 1963 I invented costume jewelry for the beautiful people. I was lionized by them, and I became one of the most splendidly beautiful of them. Handsome, tall and thin, sitting in the back of my vintage Rolls with matching driver, wearing my floor length leopard or monkey or unicorn coat, all of which have disappeared. Today I’m the same, only less lionized, less beautiful and less splendid and I’m here to sweep you off your feet. [He picks her up and sings a cappella:] Just around the corner, there’s a rainbow in the sky / So let’s have another cup of coffee, and let’s have another piece of pie. [Speaks:] I’m hungry.

If a prince comes, he will be less than a prince. If redemption comes, it will be less than redeeming. Compromised redemption figures into the broader structure of Bogeyman. The play concludes with a gay couple embarking to Mars, where, they say, they can get married and have five children. The epilogue shows them on Mars. The couple kiss, and down comes a baby (doll) from the fly space. Nearby, a boy—is it Billy?—socks his hand into a baseball mitt, the sound of which is amplified and given a “reverb” effect. A cappella and at the speed of a dirge, someone sings “Take me out to the ballgame.” The boy notices his father lying on the ground and calls out to him, alternately reaching his arms out to pick his father up and then going back to punching his mitt. The lights dim, and our last perception is of hearing the fist hit the mitt, which, distorted, now sounds like someone’s footsteps echoing slowly down a bare corridor. Even in the Martian sanctuary—a “solution” that was a pathetic fantasy to begin with—an ominousness and solitude intrude.

When the couple first land on Mars, one of them delivers a line at which several people in the audience cheered: “Kiss my ass, Pete Wilson: We’re here to stay.” But why cheer at this? They’re on Mars, which would probably suit Pete Wilson just fine. Abdoh fails when he lets his impulse to make a statement, just for a moment, get in the way of his impulse to be, as he calls himself, a “dramatist in the form of …symbolist writers.” The statement is undercut, but it’s hollow to begin with—not because it’s a bad sentiment, but because it is expressed prosaically. Fortunately, such remarks are rare in Abdoh’s work, and one sees fewer and fewer of them as it progresses.

The Law of Remains

The Law of Remains starts out in stillness and quiet. The set for most of the show is a flat stage littered with what look like dead tree trunks, their jagged branches jutting into the air. A figure with curly blonde hair, a woman, hangs from a rope, center stage. Far upstage right, Tom Pearl, who plays Jeffrey Dahmer, sings a cappella, “Old Mammy Redd of Marblehead, sweet milk could turn to mold in churn / an evil bent, with dire intent, practiced in dark her dreadful art / Old Mammy Redd of Marblehead, hanged on a tree till she was dead.” Dahmer falls, as amplified music starts to increase in volume to rock concert levels. An Andy Warhol figure emerges slowly and positions himself at a mike. A rush of sound begins and leads almost immediately into an ensemble African dance.

Warhol, Dahmer explains, is making a movie about him. “I killed 17 men,” he explains, “Andy Warhol is making a movie about my life story. I’m playing myself. It’s an Indian movie. An Indian melodrama. Andy’s stingy, Andy smells. Andy, do you have a lendable dollar?”

“Come by the factory,” Warhol tells him.

Just about everything ever written on The Law of Remains mentions that its structure is taken from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. The work is divided into seven sections, the seventh of which marks Dahmer’s arrival in heaven, after having passed through the first six sections, which constituted the Underworld—although Dahmer, one might argue, was a walking Underworld, and, indeed, his heaven has more than a hint of the Underworld in it. The structure of The Law of Remains, then, does parallel roughly the Egyptian belief that souls had to pass through a dangerous Underworld in order to get to their heaven, the Field of Reeds. In this sense, the play mimics Egyptian eschatology. The Book of the Dead, however, is not a map of progress through phases of the afterlife but is a collection of spells, about 200 of them, which have been arranged in varying orders depending on the time period and on whose collection of spells you were looking at. There are spells for preventing a man’s decapitation in the realm of the dead, for not dying again in the realm of the dead, for being transformed into a lotus, and so forth. None of this is in The Law of Remains. The inspiration, it seems, came more from eschatological beliefs of which the Book of the Dead is a part, rather than from the book itself. Abdoh also has Dahmer invoke the Egyptian goddess Ishtar, which is particularly apt given that she was alternately known as a mother goddess, a goddess of love, and also a goddess of war—an emblem for a play about sexual violence.

The Law of Remains. L to R: Juliana Francis, Steve Francis (behind her), and Tom Pearl as Dahmer. Photo: Paula Court

Alisa Solomon did not like the show. “An expensive tantrum,” she called it in her review for the Village Voice, and noted that “Even in [the play’s depiction of] heaven…there is no relief from Abdoh’s bludgeoning insistence that love is lethal.” Her main criticisms were: that the rage is monotone, eventually causing a numbing that strips the piece of emotion; that it lacks subtlety, as she cites a voice that, over the noise, cries at one point, “This is America”; and that many of the aural and visual images are misogynist.

The accusation of misogyny is remarkable, given that the play is about a male psychopath whose victims were male. And in fact, the images of the show overwhelmingly depict violence against men—Dahmer repeatedly stabbing an near-naked man lying on the floor and devouring his flesh; the Laotian boy who escapes, nearly naked and bleeding from his anus, getting returned to Dahmer by the police. The image of Dahmer stabbing and eating a man, with blood all over the floor and all over Dahmer’s face, is recurrent.

Not only does the show consist of much found material, interviews and text, but again, it’s not something that solely targets women. There are hostile references made to women, but the gender certainly isn’t singled out as something hateful. Nor are men the only people who get to inflict violence on men, as, at one point, Juliana Francis (occasionally playing Dahmer’s mother) spanks a man’s bare bottom as he stands on his hands and knees like a dog.

The “This is America” moment, broadcast by an unseen person, rushes by; it’s not pedantic, it’s ambient. On the couple of occasions when Dahmer says it, it lacks credibility, to say the least. It’s not even comparable to the Pete Wilson reference in Bogeyman; the phrase doesn’t draw attention to itself, and it’s not a political statement, as in: “Look what’s happening in America; we have to do something.” “America” is just one more debased signifier in a world where nothing—nothing—is safe, sacred, or respected.

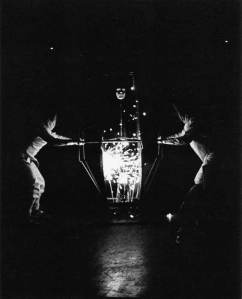

Images abound that, I imagine, come from the S&M club scene, alarmingly weird and discomforting. A woman with pierced nipples puts flammable sticks through them and lights the sticks; Juliana does a strip club dance, mirrored later by a Hispanic man in lingerie, who introduces himself as an “infected fag,” before mooning the audience and giving his butt crack a prolonged and luxuriant stroke. The audience also becomes involved in the culture when, at one point, a woman in a harsh, dominatrix tone of voice orders it to relocate for the next sequence of scenes. “Audience: stand up, move forward, turn right,” she barks, and, seeing little motion, she yells it at the audience repeatedly, with more than a touch of hostility. The White Room sequences, presumably at Warhol’s “factory,” also smack of an S&M club. Harsh, bright lights illuminate an all-white playing area that is separated from the audience by the wire wall of a cage.

More rarefied pictures are integrated into the degraded scene. At one point, in the White Room, Abdoh stops the action and places two actors in an inverted pietà: one man wearing fake breasts has another man—naked but for his army boots—lying stomach down on his lap. It would be a tableau were it not for the slow movement of the man wearing the fake breasts, sporadically and spastically caressing the leg of the naked man. There is no dialogue or sound, but for the amplified sound of someone sobbing; they are lit in a dramatic chiaroscuro.

Traits from the other works abound in The Law of Remains. There are probably more sick jokes than in any other—“What kind of flower did Jeffrey Dahmer give his prom date? Tulips.” Humor is written into the diction of horrific dialogue. Three characters speak about Dahmer’s preference for black boys, and they stumble on the syllables “dimity dab.”

PETER: Afore he discovered this here mistake, the cops discovered him. Well, they found out he was only killing niggers and they was a goin’ to run him for mayor. He felt so dimity dab bad about goofin’ up the recipe that he wanted to get up and start all over again, and I’ll give you three guesses where he is now…

JULIA: Dimity dab. You trying to tell me this here Snarling [referring to Dahmer] is prowling around these parts?

PETER: You’re dimity dab tooting. I’m meaning to tell you.

Verbal lazzi are inserted in a way that simultaneously subverts the terror of the theme while actually making the discussion, and one’s own reaction to it, all the more disturbing. Gory textual references to plastic surgery, also heard in Hip-Hop and Bogeyman, occur in The Law of Remains—Dahmer, in heaven, decides he wants to get a face lift. A CPR video in The Blind Owl is also used in The Law of Remains, with a different voice dubbed in, I think, and with a terror that is far more bludgeoning than the subtle creepiness it has in the film. The CPR program shows a female medical specialist respirating a baby doll, while in the theater a line of stone-faced women bash baby dolls against the floor.

Law of Remains. Photo: Paula Court

Again, there is an uncomfortable condemnation and complicity in using hardship and pain as a stimulus for culture. The Law of Remains takes a critical approach to Warhol’s decision to make a movie about Dahmer. Throughout, Dahmer asks, “Andy, what’s going to happen to me at the end of the movie?” The question is unanswered for much of the play, but then Warhol forecasts that Dahmer will make a heap of money, that everyone will know him, that he’ll be “a new idea…a new look…a new pair of underwear…” But at the same time, Abdoh himself is making a play about Dahmer. The Law of Remains gets a considerable amount of potency from the common knowledge that events depicted in it are known to have actually happened. In one scene, the names, ages, and ethnicities of all Dahmer’s victims are recited, with an amplified whisper of a refrain: “Soft sadness of death.” Soft is an odd choice of words here, but it somehow works as a movingly elegiac section. One could criticize it as a facile way of provoking an audience reaction, or applaud its simplicity; condemn it as exploitative or praise it as a touching homage to the victims.

Much could be written about Abdoh’s decision to show Dahmer making it to heaven, and about Abdoh’s vision for what Dahmer’s heaven would look like. Not surprisingly, heaven for Dahmer isn’t a conventional or traditional place. The tail end of Warhol’s forecast for Dahmer is that he’ll die in the electric chair, go to heaven, see his parents and his dog, and become “a Mexican junkie heartthrob dancing in a uniform of human skin and there’ll be no innocent bystanders.” Dahmer hears this and rejoins: “And we’ll all be guilty of everything.” Universal guilt is a perfect foundation for conceiving Dahmer’s heaven.

When Dahmer actually arrives in heaven, he writes letters to Bridget Geiger, his prom date from Revere High, that describe his new home.

The cadets of death mark you and they stare at your deprived future…God is a Puerto Rican drag queen with a frozen erection under a winter sun. He calls himself Lola Beltran. I see Sirhan Sirhan in my dream. I see male combatants, leprosy, abandoned children, leprosy, and the wounded. I crave optimum child mutilation films…Do you remember Ronald Reagan and the killers? He’s here now in heaven. Dressed in the Old Glory, he’s become a fuckable doll. I study his moves. We drink tea and sympathy with an avid squeak of joy. We yelp the baseball scores over the radio…I’m a Mexican heartthrob now. I’m the monkey and the jackal. My eyes light up like a pinball. Like a pinball. Like a pinball…Dear Bridget, here in heaven the government falls at least once a day, and every night I am woken up by a vertigo of dead languages and a murder of crows that shine like ice in the winter sun. Last night, a hot rod, piloted by a debased and brutal angel, screamed through a pregnant Ronald Reagan, leaving behind a wake of blood and afterbirth. Tonight I threw out a blast of condoms with a sad cheer. Tomorrow night, I will have a face lift. An incision will be placed in the hairline, and the skin lifted forward and upward from the temporal bone. All my wrinkles will be removed. I will feel no pain. I will be young again, happy again, free again. Yours, Jeffrey.

Much has been omitted from the above passage, but it still conveys the insane mix of humor, pathos, and simply bizarre imagery that Abdoh is so proficient at capturing. And it’s not an atypical mix of ideas from reality with ideas from the imagination. The line about Ronald Reagan’s being a sex doll, for example, is probably inspired, at least in part, by reports that Dahmer first tried to suppress his psychopathology by stealing a mannequin from a department store and carrying his fantasies out on it, rather than living people.

The passage incites a question that itches beneath the whole of The Law of Remains: why is Reza Abdoh drawn to Jeffrey Dahmer? The outlooks are not at all analogous—Dahmer was an amoral sadist, and Abdoh, for all the radicalism of his approach, is essentially a liberal humanist disgusted by the cruelty he depicts. There is a line of sinister excess and sexualized cruelty that stretches from the Captain to the father in Bogeyman, from Bogeyman’s father to Dahmer. Moishe Pipik bears a physical resemblance to the Captain and the father, but Pipik has, in the end, a vulnerability and humanity that the others lack. Pipik’s obesity—obesity being used as a trope for that which lacks restraint—is a fat suit that is, in the end, shed. Pipik exists and struggles in a moral universe, while the three bogeymen of the trilogy remain what they are, physically and spiritually. Dahmer dies, but he’s the same person in a different locale—besides, if we remember the frame of the Book of the Dead or of Egyptian eschatology, then the implication is that Dahmer is, in a way, dead from the start of the show. The first six sections are the Underworld, the seventh is heaven.

The trilogy, then, revolves around the idea of the bogeyman—of representations of a demonic archetype who takes sex and love and mixes them with cruelty and loathing. It is not a coincidence that the two of the monologues quoted from Hip-Hop and Law graphically refer to cosmetic surgery, which in the United States has so often been reduced to an act of self-mutilation in order to conform to Barbie Doll standards of beauty. The newly “manufactured” person of beauty conceals an act of violence–the incision in the hairline, the skin lifted forward and up from the temporal bone. Elective surgery, elected violence. The bogeymen use the words or physical representations of sex and love, but emptied of all that made them good. Sex and love become cruelty and loathing. The trilogy immerses itself in this inversion more and more as it moves from Hip-Hop to The Law of Remains. And part of what makes the inversion so threatening is the degree to which it is already being enacted in our own society. Abdoh draws on examples of the real-world constantly—in the image of the dictatorial patriarch; in the images of (sadomasochistic) bondage and discipline; in sexism, racism, anti-Semitism, and homophobia that disguises itself as morality. Abdoh drew attention to this himself in an interview in Akzente-Zeitschrift für Literatur, when he spoke of “the strange schizophrenia in the moral evaluation of violence and destruction.” When is violence permissible, and when is it not? Where does violence exist without being noticed? Violence in the trilogy is part of the process of sexual repression, and it is a result of sexual repression. Dahmer, Abdoh believes, is “a by-product of the stigmatization which is regarded as normal in this society”—a byproduct of the stigmatization Dahmer felt, Abdoh says, as an unskilled worker and as a gay man.

The inversions of the trilogy haunt all the more because sex and love already can contain elements of their opposite: as Bataille, pointed out,

The domain of eroticism is the domain of violence, of violation…The whole business of eroticism is to strike to the inmost core of the living being, so that the heart stands still. The transition from the normal state to that of erotic desire presupposes a partial dissolution for the person as he exists in the realm of discontinuity. Dissolution—this expression corresponds with dissolute life, the familiar phrase linked with erotic activity…The whole business of eroticism is to destroy the self-contained character of the participators as they are in their normal lives.

Abdoh, in Hip-Hop, Bogeyman, and The Law of Remains, takes the counter-currents that are part of sex and love and amplifies them until they destroy what is around them, self-destruct, or both.

Law of Remains. Photo: Paula Court

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

Comments are closed.