Life Be Not Proud

Britain’s quirky Improbable Theatre lets Death off the hook

By Daniel Mufson

Originally published in The Village Voice, 11 Nov. 2003.

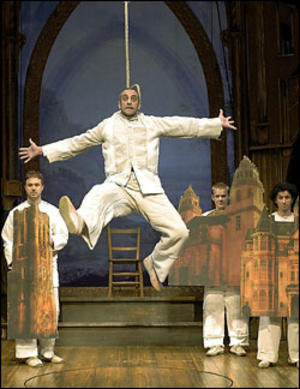

You keep me hanging on? Hanging Man at BAM. Photo: Richard Termine.

Hanging Man, the Improbable Theatre’s latest concoction, stops medieval architect Edward Braff in the middle of his attempt at hanging himself and leaves him dangling—alive—from the rafters of the church he’s designed.

Death, played by a female midget in a gray business suit, rejects his yearning for the hereafter. “A great death is like a beautiful dialogue,” she scolds. “It’s a relationship. When did you see me, architect? When did you hold me?”

That’s about as deep as the questions get during the 90-minute examination of Braff’s life and the tumult caused by his interrupted suicide. Despite ruminations on mortality, the production hardly rouses a shudder even when Death looks at the audience and says, “You’re all alive. But you won’t be forever. That is the truth.” Other attempts at big thoughts come when performers break character to describe dreams about their own deaths. One dreamed he was stabbed in his childhood home; the other, that she overdosed on heroin. Meanwhile, I had a flashback to the scene in Annie Hall where a self-inflated actor, flirting with Annie, says he’d like to die being torn apart by wild animals. “Heavy,” Woody Allen’s character says. “Eaten by some squirrels.”

The Improbable Theatre clearly feels more comfortable joking around than grasping at profundity. From the start, the actors enter the stage in costumes modeled on the commedia dell’arte character Pulcinella. Their physical agility is well suited to commedia-like humor, and the show is not without laughs, but the company’s reputation for improvisation, at least from the evidence of Hanging Man, is mostly unfounded. Aside from the lamentable singing of tin-eared Rachael Spence, the actors adeptly execute the tasks set for them by the show’s creators, Phelim McDermott, Lee Simpson, and Julian Crouch. The performers breezily mix smiles and winks to create a chummy chemistry with the audience. But the themes the company toys with—death, creativity, risk—demand a spiritual acuity utterly lacking in the text. For a man committing suicide, Braff sounds remarkably devoid of anger, bitterness, or melancholy. McDermott and his fellow cast members provide not so much a psychological portrait of him as a thumbnail sketch. There’s a wealth of material to explore here, but the evening still manages to feel padded with gags and choreography that go on longer than necessary.

By way of comparison, British playwright Peter Barnes did a far better job with similar subject matter in Red Noses, which tracks a clown troupe making its way through France during the Black Plague of 1348. Hanging Man mostly ignores its medieval setting; the ensemble, anxious lest the audience miss the immediate relevance of the platitudes, makes anachronisms and out-of-character narration the rule rather than the exception. By the time Braff dies, the story has become a parable about a successful artist “trapped in the prison of [his] own reputation.” Braff must learn to love life before he can leave it. It doesn’t make much sense, but by now we’re ready for any excuse to send Braff on his way.